- Home

- Brenda Novak

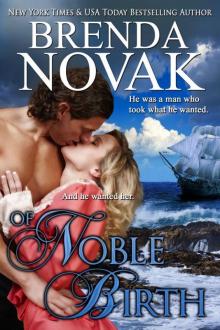

Of Noble Birth

Of Noble Birth Read online

Of Noble Birth

by

Brenda Novak

Electronic Edition

Copyright © 1999, 2011 by Brenda Novak

Smashwords Edition

Without limiting the rights under copyright reserved above, no part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in or introduced into a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form, or by any means (electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise) without the prior permission of the copyright owner.

Please Note

This is a work of fiction. Names, characters, places, and incidents either are the product of the author’s imagination or are used fictitiously, and any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, business establishments, events or locales is entirely coincidental.

The scanning, uploading, and distributing of this book via the internet or via any other means without the permission of the copyright owner is illegal and punishable by law. Please purchase only authorized electronic editions, and do not participate in or encourage electronic piracy of copyrighted materials. Your support of the author’s rights is appreciated.

Cover by Kim Killion

eBook design by eBook Prep www.ebookprep.com

Thank You.

Dedication

To my husband, Ted.

After fifteen years and five wonderful children,

I still see fireworks.

Acknowledgements

Heartfelt thanks go to my husband’s aunt, Ruth Carlson, and our good family friends, Bonnie Severietti and Russell Bilinski, for giving me the kind of support I needed at a critical time while writing this book. Appreciation and love go to my mother, LaVar Moffitt, and my husband’s mother, Sugar Novak, for believing in me through the times I scarcely dared to believe in myself. And last but not least, I owe my sincere gratitude to my agent, Pamela Ahearn, who helped make my dream a reality.

Prologue

Bridlewood Manor

Clifton, England

December 2, 1829

“The babe’s deformed,” the midwife gasped, nearly dropping the slippery newborn.

“What do ye mean?” Martha Haverson rounded the bed in alarm.

“Look at ‘is arm. ‘Tis no more than a stump.”

The housekeeper stared at Mrs. Telford’s moon-shaped face before letting her gaze slide down to the squalling child. Just as the midwife had said, one tiny limb flapped about, ending just above the elbow, as though a surgeon had amputated the rest.

“What?” The mother of the newborn craned her neck to see the child. A moment earlier she had seemed oblivious as she moved listlessly on the bed, all color gone from her fine-boned face, her lips a pallid gray. Now her eyes sprang open with a look of panic in their violet depths. “Deformed did you say? My son’s deformed?”

Martha watched anxiously as Her Grace’s eyes sought the child in the midwife’s hands. After five years and as many miscarriages, the duchess had finally produced an heir. And what a long, difficult birth it had been! Martha thought her mistress deserved a moment of triumph before further worries beset her, but Her Grace spotted the baby’s club-like limb before the midwife could shield it from her view.

“No! No!” she moaned. “My husband hates me already. What will he do?”

Martha took the baby into her strong arms, and she and Mrs. Telford exchanged a meaningful look, sharing the lady’s trepidation.

“‘E won’t do anythin’ but be glad the wee babe’s a sweet, healthy boy,” Martha assured her, reaching down to squeeze her mistress’s hand.

The baby let out a piercing howl that seemed to contradict her words.

“You don’t know him,” the duchess whispered. The revelation of the baby’s flaw seemed to sap what little strength she had left. She let her head fall back and her eyes close as a tear rolled back into her thick, dark hair.

“Don’t fret so, Yer Grace,” Mrs. Telford advised. “Yer in a bad way an’ need yer rest. ‘Tis not good for ye to stew so.”

But Martha knew that the duchess no longer heard, much less understood, either of them. She remained somewhere inside herself. Her lips moved without making a sound, as if in prayerful supplication, and she tossed restlessly on her pillow.

“Don’t just stand there. Help me.” The midwife scowled at Martha, making her realize she’d been standing motionless, staring at the duchess. Her mistress did not look well. The housekeeper doubted she would last the night.

“Will she live?” Martha whispered.

Mrs. Telford sent an appraising glance at the duchess’s face, the harsh lines around her own mouth deepening into grooves. “I don’t know. But ‘tis not doin’ ‘er a bit of good, ye standin’ there like that. ‘Tis time to clean the whelp up.”

Sternly reminded of her duty, Martha pulled away from her mistress’s bedside and headed off to bathe the new arrival. His small weight felt good in her arms. She had been unable to bear children herself, at least any that lived beyond their first month, and had been looking forward to having a little one in the house. But when she reached the small antechamber where a bowl of tepid water waited and began to sponge the child off, she couldn’t escape a heavy sense of loss. Poor Duchess. Heaven only knew that her life had not been easy since her marriage to the Duke of Grey stone.

“Mrs. ‘Averson?” It was the tweenie, the least among the least of the maids.

“Yes, Jane?” The housekeeper paused from her ministrations to look up at the gangly young girl. Only twelve, Jane was all arms and legs and as shy as she was young.

“The master would like to see ‘is son,” she said, slightly out of breath.

Martha could tell by the uncertainty in Jane’s eyes that all was not well. So the duke already knows, she thought, wishing Mrs. Telford had kept her voice down. The walls had ears. Evidently someone had already carried tale of the baby’s arm to the master.

“An’ where is ‘e?” she asked. “I’ve barely begun to bathe the babe. An’ ‘e should be allowed to suckle before—”

“I’m beggin’ yer pardon, Mrs. ‘Averson,” the jittery girl interrupted. “‘Is Grace demands we bring the child right away, lest we both lose our positions. ‘E’s waitin’ in the library. Mrs. Telford is on ‘er way there.”

Martha bit her lip and glanced over her shoulder in the direction of the duchess’s room. “Very well. Fetch a blanket. It won’t do for the babe to catch a chill, poor little love.”

* * *

Albert Kimbolten, Duke of Greystone, was pacing across an exquisite gold and blue Turkish rug when Martha entered. Massive mahogany bookshelves crowded with leather-bound volumes lined three walls. They were dusted once a week, though rarely used. A fire crackled comfortably in the fireplace. The midwife sat in a Chippendale chair near a long, rectangular table, the fingertips of both hands pressed together, her lips pursed.

At Martha’s entry, the duke turned to face her. His brows knitted together, a solid black line atop flashing blue eyes, making Martha shiver as though a cold draft suddenly swept the room. The heir had been born, and she was to present him to his father. But this was nothing like the moment she had long anticipated. There were no smiles of delight, no proud glances—only anger, seething from the man before her with all the force of a tidal wave.

Martha drew a shaky breath. “Yer son, Yer Grace.”

“Lay it on the table.” Greystone did not bother to watch as Martha reluctantly deposited her charge as directed. Instead, he stared into the black night beyond the window that mirrored his savage-looking visage. “That will be all.”

Martha backed away. Only the fear of making matters worse forced her to take one step and then another until she passed into the hall. After closing the door she paused on the other side to listen to the words

floating to her ears from within the library.

“What are you telling me?”

Martha could hear the tremor in the duke’s voice even through the door.

“As I said before, yer son is deformed,” the midwife explained. “‘Tis not uncommon. Such things happen now an’ again. From the look of it, the babe will never ‘ave the use of ‘is right arm.”

“And his mind? Is it similarly... defective?”

An interminable pause.

“I cannot tell, Yer Grace. ‘Twas such a difficult birth...”

“I see. Will he ride? Hunt?”

“‘E may do neither. I ‘ave no way of knowin’ ‘ow the child will develop. In all ‘onesty, Yer Grace, I am far more concerned with yer lady—”

“My lady? After five years, this is what she gives me. A cripple. A laughingstock!”

The sound of shattering glass made Martha jump. The baby began to wail, and she fought the urge to march in and fetch him.

“But Yer Grace, the duchess ‘ad no—”

“Leave me!” he shouted above the cries of his son.

Something—his fist?—crashed down onto a table. A startled yelp escaped the midwife, followed by the thud of other articles being hurled against the walls or fireplace. Then the midwife scuttled from the room, slamming the door behind her.

Martha acted as though she were just approaching. “Mrs. Telford, is somethin’ wrong?”

“‘E’s gone mad, I tell ye. Simply mad.” The midwife threw up her hands. “Ye’d best leave ‘im for a time. I’ve got my work cut out for me with the duchess.”

Martha wavered as Mrs. Telford fled down the hall. She longed to enter the room and rescue the crying infant, but was loath to further fuel His Grace’s anger, for the baby’s sake as much as her own.

Silence jolted Martha out of her quandary. One minute the baby had been wailing uncontrollably; the next, nothing. She pressed closer to the door, holding her breath. Not a single sound reached her ears.

Panic propelled her forward. She burst into the room and her eyes took in the tall, immaculately dressed duke leaning over his son. One large hand covered both nose and mouth of the newborn infant.

He’s killing the lad. He’s killing him! her mind shrieked as she flew at her master. Scratching and clawing at Greystone’s manicured hand, she tried to provide the child with air.

“Get away!” he snarled.

But Martha fought for the child’s life with the same desperate longing she felt for her own dead sons, and finally the infant let out a howl.

The duke backed away, his face red, the veins in his neck bulging above a white collar. “I’ll kill you for this!”

“Please,” Martha gasped. “‘E’s yer son.”

Greystone gave a derisive snort. “I could not have fathered this... this deformity. I will not have him. Do you hear? He will never be my heir.”

Martha gulped air into her lungs as the duke’s words registered in her mind. How could a man be so cruel? Finally she asked softly, “May I take ‘im, then?”

Crimson suffused the duke’s face. “Without me, without my reference, you will be unable to find work. How will you provide for a sick husband and a deformed babe?”

“I don’t know.”

“Fool! I’m tempted to let you starve the child for me, let you watch him die a slow death, but I cannot take that chance. Should you manage it somehow, as soon as he grew old enough, the two of you would be on my doorstep crying ‘Inheritance!’ ‘Heir!’“ He lunged at her. “Never!”

The air stirred near her ear as Martha whirled away. She fully expected to feel the duke’s long fingers close about her neck, pinching off her own breath, when suddenly she heard an odd gasp and turned in time to see him trip on the plush rug. His head struck the corner of the table as he toppled over like a felled tree.

Martha stared at the limp body lying unnaturally at her feet. Blood oozed from a wound at his temple. What now? she thought as panic rose like bile in her throat.

Bending to search for a pulse, she felt a faint beat at his throat and slowly let out her breath. But the fact that he yet lived posed another problem. Suppose when he awoke, he blamed her for his fall—blamed her and the baby.

Martha’s gaze left, the duke’s ashen face and moved to the squirming bundle atop the table. Its cries registered in her mind. Greystone had tried to kill the baby. The duchess was likely dead already.

Without further deliberation, Martha pulled the infant into her arms and fled the room. She ran through the long halls of Bridlewood Manor, past bedrooms and sitting rooms and libraries, to the back stairs and down, and finally through the kitchen and beyond into the cold winter’s night.

Chapter 1

Manchester, England

March 5, 1854

“Let me out! Please, Willy, let me out!”

Alexandra’s voice rose to an unnatural, high-pitched scream. The walls and lid of the trunk pressed in upon her like a coffin, the heavy darkness crushing her chest like a thousand pounds of sand. Stifling. Suffocating. Terror gripped her as she struggled for breath, pounding her fists on the locked lid of the old steamer trunk.

In her panic, she almost failed to notice the sliver of light that penetrated the blackness. When she did see it, her gaze clung to it as tightly as a drowning man might clasp a life preserver to his breast. Age and use had left the dome-shaped lid slightly warped. Surely air could pass as well as light. Still, Alexandra had to force herself to breathe slowly, to resist the hysteria that threatened to overwhelm her.

She ceased her pounding.

“Papa?” she wept. She hadn’t called Willy “Papa” for years, but she felt like a child again, like the little girl who used to love him, trust him. “Are you still there?”

Silence. Alexandra concentrated on the beam of light. The tiny slit didn’t provide much air. She could hardly breathe. Where was he? There had been no sound for several minutes. Had he left her?

“Oh no, please,” she whispered. Certainly even Willy wouldn’t abandon her this way. Her stepfather never hurt her when sober, rarely spoke to her, in fact, but his love of gin exposed another side of his nature. The beatings that had begun shortly after her mother’s death five years ago had become increasingly common and more violent as Willy’s dependence upon alcohol grew. Now drunkenness was his way of life.

Alexandra tried to shift her weight, but the trunk was too small to hold a nineteen-year-old. She was crammed into it with her long legs tucked under her chin, her arms squeezed tightly against her sides. Her right hip supported the whole of her weight, causing pain to shoot down her leg until, mercifully, the restricted blood flow made it go numb. Still, her head throbbed; whether from the punishing blow Willy landed when he had first set upon her, or from the fit of weeping that had overtaken her when he had forced her inside her mother’s steamer trunk, she did not know.

A shuffling sound alerted her to the fact that she was not alone after all. She tried to hold her breath so she could hear from whence the movement came, but her involuntary gasps continued.

“Willy? Please, open the lock.” Alexandra hoped a calm appeal would evoke some response, but she received no answer. She felt as though she were walking a tightrope of sanity. One wrong word could turn her stepfather away and send her plummeting into panic once again.

“Are you still there? Don’t leave. Please. If you don’t let me out, how will I work? You know we have a half dozen shirts to finish today.” She paused. “Don’t you want to get paid?”

“Shut your trap, wench,” Willy growled. “I can’t stand the sight of you.”

“But I’ll go directly upstairs. I promise. You won’t so much as see me.” Her body ran with sweat, but Alexandra fought to control her fear. At least Willy was there. At least he was talking to her. So far, she was managing to keep her precarious balance.

“We’ve got only until noon to finish the shirts. The skirts for Madame Fobart’s are due right after. You said so yourself,�

� Alexandra pleaded. “I’m the quickest seamstress you’ve got, aren’t I? I’ll work hard, you’ll see.”

Willy cursed, but Alexandra could tell his anger had lost its edge. Her approach was working, it seemed. “Madame Fobart gives us the bulk of our work. We certainly don’t want to lose her.”

“To hell with bloody Madame Fobart!”

Willy kicked the trunk, causing Alexandra to yelp in surprise as he bellowed in pain. “To hell with it all!” he croaked.

“You don’t mean that.” Alexandra forced the words out above the heavy thumping of her heart. “We’ve got a lot of business now, and soon we’ll be making good money. But I can’t finish our orders if you don’t let me go.”

For the briefest moment, she wondered if they could finish their work on time in any event. The order Willy had brought from Madame Fobart’s was double the usual, and with the work came the demand that the skirts be made up and delivered in less than two days. Though Alexandra and the other needlewomen had sewn well into the night, they still had much to do. But how would Willy know that? He had left for the tavern while the candles yet burned in the garret above, and she and the other women worked tenaciously on. Could he even begin to comprehend the mounting pressure of each new deadline when his time was spent sleeping off the effects of the previous night’s bottle? Willy never appeared until late in the day, and then only to criticize, grumble, and complain. That he procured any clients at all was indeed a great wonder.

Silence again.

“Willy?” Rational thought bled slowly from Alexandra’s mind as her head began to spin. There was so little air. Work. She had been talking about work. But why? She no longer remembered, except that her life was one monotonous round of stitch, stitch, stitch. Even now her mind called her fingers to sew—but it was so dark.

Falling For You

Falling For You A California Christmas

A California Christmas When I Found You

When I Found You Sanctuary

Sanctuary Home for the Holidays (Silver Springs)

Home for the Holidays (Silver Springs) One Perfect Summer

One Perfect Summer Christmas in Silver Springs

Christmas in Silver Springs Before We Were Strangers

Before We Were Strangers Coulda Been a Cowboy

Coulda Been a Cowboy Blind Spot

Blind Spot That One Night

That One Night The Perfect Murder

The Perfect Murder Falling For You (Dundee Idaho)

Falling For You (Dundee Idaho) In Close

In Close Home for the Holidays

Home for the Holidays A Dundee Christmas

A Dundee Christmas The Perfect Couple

The Perfect Couple On a Snowy Christmas

On a Snowy Christmas Her Darkest Nightmare

Her Darkest Nightmare When We Touch

When We Touch A Winter Wedding (Whiskey Creek)

A Winter Wedding (Whiskey Creek) The Perfect Liar

The Perfect Liar Dead Silence

Dead Silence Baby Business

Baby Business Shooting the Moon

Shooting the Moon A Home of Her Own

A Home of Her Own Taking the Heat

Taking the Heat Of Noble Birth

Of Noble Birth Every Waking Moment

Every Waking Moment Face Off

Face Off Expectations

Expectations Hello Again

Hello Again When Snow Falls

When Snow Falls Come Home to Me

Come Home to Me Be Mine at Christmas

Be Mine at Christmas The Secrets She Kept

The Secrets She Kept In Seconds

In Seconds No One but You--A Novel

No One but You--A Novel Dear Maggie

Dear Maggie Hanover House: Kickoff to the Hanover House Chronicles

Hanover House: Kickoff to the Hanover House Chronicles When Summer Comes

When Summer Comes Discovering You

Discovering You Inside b-1

Inside b-1 Body Heat

Body Heat Sweet Dreams Boxed Set

Sweet Dreams Boxed Set A Family of Her Own

A Family of Her Own Stop Me

Stop Me Inside

Inside The Heart of Christmas

The Heart of Christmas In Seconds b-2

In Seconds b-2 Through the Smoke

Through the Smoke The Other Woman

The Other Woman We Saw Mommy Kissing Santa Claus

We Saw Mommy Kissing Santa Claus 05 Take Me Home for Christmas

05 Take Me Home for Christmas Killer Heat

Killer Heat This Heart of Mine

This Heart of Mine Until You Loved Me--A Novel

Until You Loved Me--A Novel Cold Feet

Cold Feet Snow Baby

Snow Baby Dead Giveaway

Dead Giveaway Face Off (Dr. Evelyn Talbot Novels)

Face Off (Dr. Evelyn Talbot Novels) Just Like the Ones We Used to Know

Just Like the Ones We Used to Know A Baby of Her Own

A Baby of Her Own Take Me Home for Christmas wc-5

Take Me Home for Christmas wc-5 Finding Our Forever

Finding Our Forever Historical Romance Boxed Set

Historical Romance Boxed Set Right Where We Belong

Right Where We Belong Big Girls Don't Cry

Big Girls Don't Cry